Tag: History of Oman

Two Pots – Colour Version.

Tombs at Manal.

Archæological site: opposite the Village of Manal.

There was some interest in this site around 2003 if I remember correctly; when a dig was carried out and most of the tombs were enclosed by a chain-link fence, but behind this on a tributary of the main wadi are more tombs.

I am not sure of the age: but what information I could find, listed it as an Iron-age site, although some of the tombs could be reused from an earlier date.

Storm clouds building over tombs.

The Pirate Coast.

Beach watch tower near Bukhā on the Khasab coastal road.

Beach watch tower near Bukhā on the Khasab coastal road.

Yashica 124G on Ilford HP5plus.

This whole section of coastline was (even a little today !) known for its piracy. Mentioned on official maps of the area as The Pirate Coast, recognised as such, all the way back to around 694 BC, when Assyrian pirates attacked traders travelling to and from India via the Persian Gulf.

One of the earliest mentions of piracy by the British came from a letter written by William Bowyear: East India Company Resident at Bushire, and his assistant, James Morley, to Henry Moore, East India Company Agent at Bussora, dated 13 July 1767

It describes a rather brutal Persian pirate named Mīr Muhannā:

“In his day, he was a major source of concern for all those who traded along the Persian Gulf and his exploits were an early factor, beyond purely commercial concerns, that led the East India Company to first become entangled in the politics of the region”

Samuel Marinus Zwemer, while traveling in the area has several interesting references about the safety of travellers: a snippet –

Oman and Eastern Arabia S. M. Zwemer: Journal entry 1907.

It may be of interest to note our mode of travel in this primitive country, where there are no beasts of prey but where every one goes armed for fear of his neighbour. I quote from my diary:

……..Our guides proceeded mounted, but with their rifles loaded and cocked; then followed the baggage-camel, to which mine was towed in Arab fashion by hitching the bridle of the one to the tail of the other; in like manner, my companion rode his beast fastened to the milch-camel, followed by its two colts.

Around 1805, the Wahhabis implemented a system of organized raids on foreign shipping. The vicegerent of the Pirate Coast, Husain bin Ali, compelled the Al Qasimi chiefs to send their vessels to plunder any trading ships of the Persian Gulf without exception. Rather lucrative because he kept at least 1/5th of the plunder for himself.

At the end of the 1809 monsoon season, British authorities in India decided to make an example of the Al Qasimi once and for all. An expedition was sent to destroy the largest of their bases and as many ships as could be found; an added bonus was to counteract French encouragement of these pirates from their embassies in Persia and Oman. By the morning of 14 November, the military expedition was over and the forces returned to their ships, suffering light casualties of five killed and 34 wounded. Arab losses were unknown, but probably significant and the damage done to the Al Qasimi fleets was severe: as a number of their vessels had been destroyed at Ras al-Khaimah.

The Pirate Coast was later called the Trucial Coast after the Treaty of Maritime Peace in Perpetuity was signed in 1853, giving the Royal Navy responsibility for the protection of shipping. It also set the seeds for what would later become the United Arab Emirates.

Basket in shadows.

Into the light.

Muscat Harbour – ship names.

Visiting Muscat harbour anchorage at the entrance to a bay overlooked by the Sultan of Oman’s Muscat palace; there has been a tradition for ships crew to paint the name of their vessel on the rocks surrounding this bay.

A lot of the names are very faded and can only be read up close from a boat, but one or two are still very distinct; HMS Perseus being one of them.

Now a problem arises:

Received wisdom says the ships name refers to:

HMS Perseus a British Parthian-class submarine built in 1929 and lost in 1941.

But there was another HMS Perseus who spent time visiting Muscat.

HMS Perseus was a 3rd Class, Protected Cruiser.

Built by Earle of Hull, laid down May-1896, launched 15-Jul-1897, and completed 1901.

On completion she went to the East Indies Station, where she spent her entire active service 1901-13.

Returned to the UK and paid off.

The diary of A. Barker whilst in service aboard the Protected Cruiser, HMS Perseus in 1901/03 at the East Indies Station. Starting from 13th September 1901, he makes several entries pertaining to Muscat.

See example of entries below.

13th After smooth passage we arrived at Muscat at 9 am. We saluted the Sultan with 21 guns which was returned.

14th We coaled ship 200 tons.

Time had been rather dull during our time up the Gulf as we had had no leave since we left Karachi so we arranged a seigning (sic) [seining or net fishing is what I think he means] party, which came off very well.

18th We received the Sultan & the British Consul on board. A salute of 21 guns for the Sultan 11 for the Consul was fired.

20th We had Divine Service which was conducted by the American Minister from ashore

21st We got the starboard bower anchor out, and then we started painting ship.

23rd We had another seigning (sic) party, which was attended by the British & American & French Consul & Mrs Cox. There being no communication from Muscat by telegraph we left Muscat on the 25th for Jask & arrived there the 26th. We left again on the 27th for Muscat.

28th We carried out our firing and arrived at Muscat. We moored ship placing spare bower on the billboard.

29th We unmoored ship and replaced spare bower anchor.

30th We left Muscat at 7.30 am with British Consul & Sultan of Muscat & 150 soldiers onboard, bound for Sur & Khora Jehoram

And another:

HMS Perseus – Light Cruiser 2,135 tons served in The Persian Gulf between 1909 and 1914:

Towards the end of the 19th Century the trafficking of arms in the Persian Gulf area had escalated to dangerous proportions. The British Government pressurised the Governments of Persia and Muscat to take action to bring this business under control. By 1897 Persia had managed to reduce the involvement of their nationals but Muscat was still a serious problem.

So this ship also visited the harbour on several occasions.

But the most interesting is this reference to a HMS Perseus crew painting their ships name in 1857, Made by members of HMS Gambia who visited in August 1958 and did the same thing.

While a few of us had thus been seeing what there was to see, or doing battle on the hockey pitch, a party of stout-hearted individuals had landed on the rocks a few hundred yards from the town where, having scaled a hundred-odd feet of mountainside, they set-to repainting the magic letters GAMBIA on the rock-face, together with the Admiral’s Flag close-by. This was not just a bright idea by one of the boys, but part of a publicity campaign which has been going on ever since H.M.S. PERSEUS painted her name on the brown rock in 1857. As a result, the cliffs either side of Muscat form what is surely the world’s biggest autograph album, for by now they are covered with the names of ships and not only R.N. ones who have visited the place.

The problem is that if the following list is correct, it would indicate that no ship called HMS Perseus existed for that time frame (1857) – so who knows.

Six ships of the Royal Navy have borne the name HMS Perseus.

HMS Perseus was a 20-gun sixth rate launched in 1776; she was the first vessel of the Royal Navy to be sheathed in copper. She was converted to a bomb vessel in 1799 and was broken up in 1805.

HMS Perseus was a 22-gun sixth rate launched in 1812. She was used for harbour service from 1818 and was broken up in 1850.

HMS Perseus was a Camelion-class wooden screw sloop launched in 1861. She was used for harbour service from 1886, was renamed HMS Defiance II in 1904 and was probably sold in 1912.

HMS Perseus was a Pelorus-class protected cruiser launched in 1897 and sold for scrap in 1914.

HMS Perseus was a Parthian-class submarine launched in 1929 and sunk in 1941 during the Second World War.

HMS Perseus was a Colossus-class aircraft carrier launched in 1944 as HMS Edgar but renamed a few months later. She was scrapped in 1958.

Steps & Post.

Steps & Box.

Forgotten bowl in abandoned building.

Tomb of the Umm an-Nar period at Shir Jaylah in the eastern Hajjar .

Entrance doors.

Half open door & windows.

Store room.

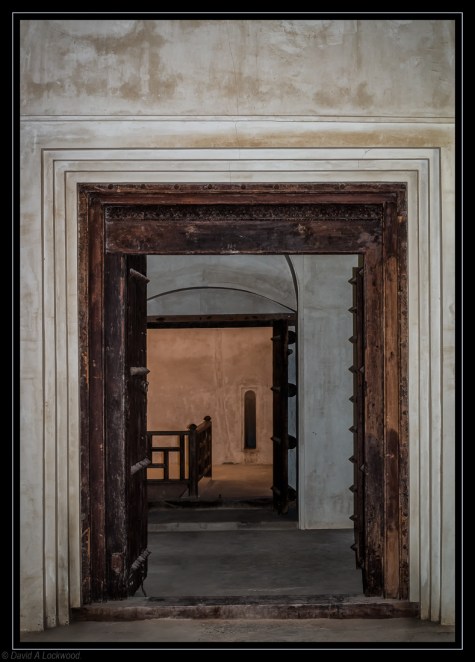

Doors within doors.

Open window with tray.

Abandoned fortified ruins.

The Devil’s Gap.

Dima wa’Tayeen in the Sharqiya region, will take you to Wadi Tayeen and at Ghubrat at Tam, the Wadi takes a dramatic turn in a breach of the Jebel Aswad range (The Devil’s Gap) from here it takes the name Wadi Dayqah.

Note: Mariners called the sea end The Devil’s Gap but it is now generally known by this name at the Wadi Tayeen end as well.

Lieut, J.R.Wellsted – Travels in Oman 1837 Vol 1. Page 41

Extracts from:

JOURNAL OF EXCURSION IN OMAN, IN SOUTH-EAST ARABIA.

by Colonel S.B. Miles Pub:1838.

&

The Geographical Journal

Vol. 7, No. 5 (May, 1896), pp. 522-537

S. B. Miles.

The town of Ghubra el Tam (sic) is very picturesquely situated on the skirt of an eminence, which, lying at the end of the valley and thus forming a barrier against the onward progress of the stream, has caused it to swerve to the northward and cut its way through the mountain range down to the sea. It has some good houses and a population of over a thousand of the Siâbiyin tribe, and is protected by a strong fort of oblong shape perched on the western extremity of the hill.

At this time there was very little water in the wadi, the unusual dryness of its bed being due to the severe and long-continued drought, from which this part of Oman had been suffering, and our party were congratulating themselves on having arrived at such an opportune time for passing through the gorge, when their joy was suddenly turned into dismay by a slight shower of rain which fell in the evening. The clouds now began to gather so ominously in the sky, that if it had not been so late I should have pushed on at once without halting. It had, however, already become too dark to permit of this, and with some foreboding—for the intensity of the heat seemed to threaten a thunder storm—we took up our quarters for the night in the habitation our hosts the shaikhs of the town had allotted to us. Had it rained heavily, as many of us fully expected, I should have had to wait here until the torrent had subsided sufficiently to allow of our proceeding through the gap, which would undoubtedly have entailed a delay of several days.

The exploration of this caňon had been one of the main objects of my journey, as it had not before been traversed by a European, so I was resolved to seize the present chance of visiting it at all risks. Fortunately, the night passed without the expected downpour, and though the morning of the 16th broke gloomily and lowery, the rain still held off, and the stream flowing at our feet had risen but slightly. After a consultation, we deemed it best to face the peril of a sudden rush of water through the gorge, and hazard the passage before the storm, which now appeared inevitable, could burst upon us and unite the rills and streamlets of the valley into a swift and overwhelming torrent. having hastily loaded the camels, therefore, we started early, and crossed the bed of the wadi, in which the water was running a little over 2 feet deep, just opposite the town. We then found ourselves at once at the entrance of the great cleft, which is as sharp and abrupt as if we were entering the portals of some monstrous castle and stood immured within its massive walls. Towering loftily, sheer and perpendicular above the narrow floor, the huge walls of rock give the appearance as if the mountain range had been suddenly split in two from the base to the summit by some convulsion of nature, exhibiting a singular illustration of impressive grandeur. The breadth of the passage here is about 100 yards, but it varies throughout its length from 500 to 150 yards, while the cliffs rise to an altitude of from 1000 to 1500 feet, as near as I could judge. The stream appeared to flow 4 or 5 miles an hour, and gradually increases in volume as we progress, being fed by the springs of water which burst from the crevices in the walls. Throughout the chasm the camels were wading nearly up to their knees.

After riding along this grand and curious gallery for a quarter of a mile, we are told to dismount, having arrived at a sort of deep step or waterfall called the Akaba. Here the camels are relieved of their baggage and saddles, and are taken along a ledge of the precipice on the left bank which leads circuitously to the bed further on, while the men of our party are let down by a rope over the projection on to the floor of the wadi below. This remarkable stop or fall in the rock offered a very serious impediment, as it was of considerable depth, while huge blocks and fragments of blue and white limestone, that had fallen from above, added lo the difficulty, and presented an obstacle which was absolutely insuperable to the camels, even when freed of their loads. The path leading to the fall, along which we had to scramble, was so rugged and slippery, and the cliff was so smooth and waterworn, that even the Arabs, who are as nimble as cats, did not find it easy work.

The solicitude evinced for my safety, not only by my own party, but also by the Siabiyin who had accompanied us from Ghubreh was almost touching, though the descent could not in fact be called perilous. Indeed, throughout my excursions in Oman, 1 always had reason to he grateful to the Arabs of my escort, and not infrequently to the local Arab shaikhs, for their zeal and self-sacrifice on my behalf. They never resented the inconvenience and fatigue 1 often caused them, but deferred without question to my wishes as to the when and the whither; while on any occasion of unusual toil or danger, they seemed to regard my safety and comfort as a main point of consideration.

At the bottom of this pass, called Al Makuba by our Siabiyin guides, we waited an hour for the camels, which, though carefully led by the drivers, did not traverse the narrow and dangerous ledge on the other hank without serious difficulty and hazard. Fortunately, however, they arrived at last in safety, and the baggage, which had in the mean time been lowered down by the Arabs, having been replaced, we mounted and resumed our journey.

“we are told to dismount, having arrived at a sort of deep step or waterfall called the Akaba.”

This is still a difficulty even in 2015 !

Extracts from:

THE COUNTRIES AND TRIBES

OF THE PERSIAN GULF.

Pub: 1919 by COLONEL S. B. MILES

Al-Sharkiya, as its name implies, denotes the most easterly province of Oman, and is bounded on two sides by the sea, on the south-west by the desert, and divided from Oman Proper by the hill range, as described above. It is mountainous to the north along the coast, the highest peak being Sohtari, which rises over 6,000 feet,and to the south-west it is more level, more fertile, and more populous.

The northern part of Al-Sharkiya is drained by the Wady Tyeen, which flows into the Gulf of Oman, while in the south the watershed throws off four streams, Ethli, Andan, Halfam, and Kalbuh, all of which unite in one and discharge into a creek a little to the east of Mahot in the Bahr al-Hadhri. This province includes three or four luxuriant and well-watered districts, the Tyeen Valley, Jaalan, Bediyeh and by some Semed al-Shan.

The first of these is a perennial and important stream occupied by more than thirty villages, and after cutting a deep chasm through the hills known to mariners as the Devil’s Gap, reaches the sea at Dagmar, east of Kuriyat.

The great valley called by the Arabs Wady Thaika, or Hail Ghaf, and known to Europeans as the ” Devil’s Gap,” a narrow cafion cut through the hills by the water of the Wady Tyeen ; the bluff on the northern side of the gap is called Nuwai, while that on the southern is called Naab.

Abandoned village first light.

Early morning – passing Jabrin Fort.

Tombs: Qubur Juhhal – Al Ayn.

Arch with Door – Ruins.

This was made on a visit to a very dilapidated building – all the plaster was very crumbly & turned sandy if touched.

Anywhere else & I would never have been allowed in; for safety reasons (read ‘jobs worth’). But this is Oman ! so coffee & dates and polite conversation with the custodian, along with an explanation that I wanted photographs before it fell-down completely 🙂